It is important to tell you that there will be spoilers in this commentary.

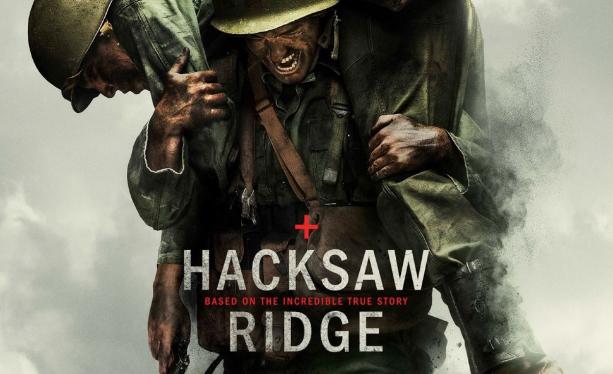

There are two religious movies out right now from Academy Award winning directors. The first, Hacksaw Ridge, is directed by Mel Gibson, and is about a young Christian man who refuses to carry a gun into war as his faith will not let him take another man’s life. The second, Silence, is directed by Martin Scorsese, and tells the story of two young priests who go to 17th century Japan to find their mentor who they have heard has left the priesthood and apostatized — meaning he renounced his faith.

The two movies actually have quite a bit in common: they both star Andrew Garfield in the lead, they both represent the main character facing challenges to his faith, and they both require the main character to put his life on the line for his faith. While the similarities are strong, it is the differences that are important to consider in regards to how Christians must act considering the challenges to publicly living out our faith.

Hacksaw Ridge tells the true story of Desmond T. Doss, who joined the Army as a medic during World War II. Unlike his fellow soldiers, Doss would not touch a weapon, as his faith precluded him from harming others. During basic training Doss was ridiculed, abused, threatened, encouraged to quit, kept from his own wedding, and even court-martialed, but he never gave in. He eventually was allowed to go to war without carrying a gun. Doss’ division was sent to Hacksaw Ridge — an extraordinarily dangerous and deadly location. Doss’ division attacked, but were eventually pushed off the ridge. Doss stayed behind and saved over 75 soldiers by carrying them from the battlefield to safety. Doss was awarded the Medal of Honor, and was the first conscientious objector to receive the honor.

Silence takes place in 17th century Japan, and follows the story of two Jesuit priests who travel to Nagasaki, Japan to find their mentor, Father Ferreira, and spread the Catholic faith. The two priests land in Japan and discover Christians are being martyred unless they reject their faith. They also realize that their mentor is now married, left the priesthood, and is helping the Japanese. Both priests are captured by “The Inquisitor,” and are told if they do not publicly reject their faith other Christians will die. One of the priests dies trying to help a fellow Christian, and the other remains steadfast as Japanese Christians are slaughtered. The Inquisitor has the remaining priest meet with his mentor who convinces him to give up his faith so that other Christians might live. The priest lives out his life working with his mentor to identify other Christians, and eventually dies without ever showing he returned to the faith. As the priest lies in his casket, the camera shows that he has a crucifix in his hand.

The differences between these outcomes are huge, and impact the way we see our faith playing out. Where Hacksaw Ridge illustrates the value of remaining faithful, Silence dangerously communicates that when you find conflict between your faith and others it is noble to hide it away and just live a “personal” and secretive faith.

So long as you believe, right?

In a post a few months ago, I wrote that “Oftentimes, we take an individualistic view of Christianity that is centered upon a personal relationship with Christ. But Christ also requires our faith to be lived out (James 4:17). Our faith is a both a personal relationship with Christ AND the public expression of that relationship.” The cornerstone of Hacksaw Ridge is to live out one’s faith no matter the cost. In contrast, Silence’s foundation was if there is a cost it is OK to not live out your faith. We are seeing Silence play out over and again in our society; a notion that faith is a personal idea to be lived in church and at home, but not welcome elsewhere. And Silence is saying that it is OK to submit. But our Christian faith is actionable, and therefore not compatible with silence (the movie or the failure to speak out).

If we are going to build a better, more moral world, then we must share the Gospel, and live it out in love. We cannot accept conditions where we compromise, are shamed, or frightened into hiding our faith. Instead, we must forge into battle proclaiming the truth so that all might have life.

I knew if I ever once compromised, I was gonna be in trouble, because if you can compromise once, you can compromise again

Desmond T. Doss